A recent assignment for my Master of Educational Technology in ETEC 500 – Research Methodologies in Education had me examining two contradictory research studies to explore how they could come up with such different findings. For me, this shone a spotlight on why it is so very important to teach media literacy, critical thinking, research skills, the scientific method and proper scientific inquiry (as oppose to science as rote learning, which too often happens), and data analysis.

In the media that we consume, we see a lot of articles and statements with bold claims that contradict each other. As a scientist, I am all too aware of how data can be manipulated to seemingly support one claim or another out of bias or at times for more nefarious reasons involving things like politics and finances. Since I have been studying educational technologies, one such topic of contradiction in research studies has been the impact of screen time on children. This is further aggravated by media outlets utilizing the research to create sensationalized headlines, often that misrepresents the data.

Recently I read one such article by Andrew Przybylski and Amy Orben in The Guardian, We’re told that too much screen time hurts our kids. Where’s the evidence? At the time of reading this, I found myself questioning the validity of the questions that were asked of the teens around their social media use, in the collection of data. I also found the title of the article to be misleading, as it mentions screen time use, yet the study focuses on social media use. While you are on your screen when using social media, screen time is a much broader topic to social media use.

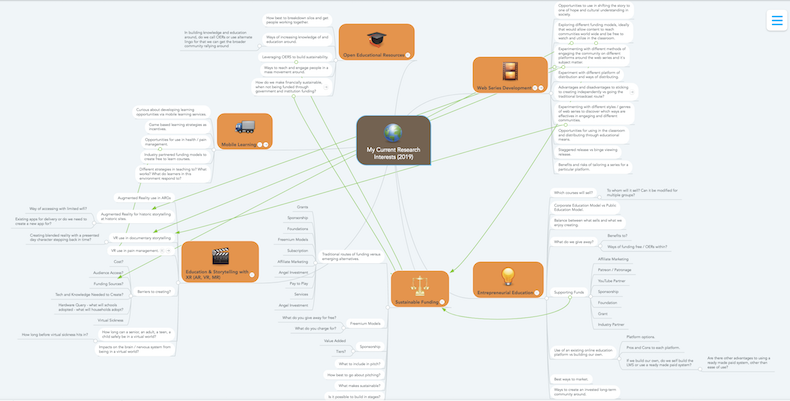

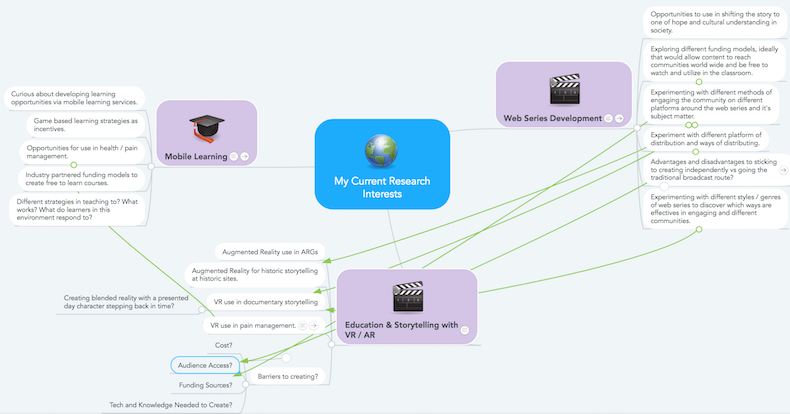

Pondering this article, made me think that perhaps we are missing the important questions here. Screen based technologies are becoming more and more an important part of our lives, and as such part of our schooling, so rather than the extreme viewpoints of ‘screen based technologies are our salvation’ or ‘screen based technologies breed evil’, the questions I wish to ask are around healthy use of those screen based technologies to find the balance both in the classroom and outside of it. While I work on screen based technologies and create both screen based stories and edtech, it is important to me that I do so in a way that is healthy for my audience and my students. I know that for myself, personally, too much of certain types of screen use gives me headaches and can make me feel anxious. Video games were like this for me as a kid, and as I had a slightly addictive nature with them, is why I now avoid them. I also know that when dealing with a concussion, I’ve had to be very careful with my screen time, as too much screen time aggravates the concussion symptoms. This is something that I wrote about in this article on Researching Optimal Screen Time Limits for Classroom Activities for Different Screen Based Activities.

Photo care of Constellate via Unsplash.

From the list of research studies that I compiled in the aforementioned article, I looked for two articles with bolder statements in their titles that appeared to contradict one another. The contradictory articles I selected were ‘Everything in Moderation: Moderate Use of Screens Unassociated with Child Behaviour Problems‘ by Christopher J Ferguson in Psychiatric Quarterly (December 2017) and ‘Screen Time is Associated with Depression and Anxiety in Canadian Youth‘ by Danijela Maras, Martine F. Flament, Nicole Obeid, Marisa Murray, Annick Buchholz, Katherine A. Henderson, and Gary Goldfield in Preventative Medicine (April 2015).

‘Everything in Moderation: Moderate Use of Screens Unassociated with Child Behaviour Problems’ by Christopher J Ferguson takes a representative correlational sample of youth from the State of Florida and assessed them for links between screen time and risky behavioral outcomes. Risky behavioral outcomes in terms of this study were classified as delinquency, risky behaviors, sexual behaviors, substance abuse, reduced grades or mental health problems. In reading this study and comparing it to Maras et al (2015)’s study, my interests were specifically in regards to correlations between screen time and mental health problems. The conclusions made in this study were that “use of screens that was moderately high, in excess of the American Academy of Pediatrics’ former recommendations of limiting screen time per day to 2 hours, but not excessive, was not associated with delinquency, risky behaviors, sexual behaviors, substance abuse, reduced grades or mental health problems. Even excessive screen use was only weakly associated with negative outcomes related to delinquency, grades and depression only, and at levels unlikely to be practically significant.”

The research study ‘Screen Time is Associated with Depression and Anxiety in Canadian Youth’ by researchers Danijela Maras, Martine F. Flament, Nicole Obeid, Marisa Murray, Annick Buchholz, Katherine A. Henderson, and Gary Goldfield, “examined the relationships between screen time and symptoms of depression and anxiety in a large community sample of Ottawa youth.” The conclusions drawn from this study are that “screen time may represent a risk factor or marker of anxiety and depression in adolescents”, and that “future research is needed to determine if reducing screen time aids the prevention and treatment of these psychiatric disorders in youth.”

Similarities that exist in both studies include the age of youth – 12 -18 in Ferguson (2017) and 11 – 20 in Maras et al (2015), large sample sizes – 6089 in Ferguson (2017) and 2482 in Maras et al (2015), and school based parent and student opt-in surveys. Difference include the communities the studies were conducted in – Florida in Ferguson (2017) and Ottawa in Maras et al (2015), the types of questions asked on the surveys, different intent between the studies – examining risky behaviour in Ferguson (2017) and examining mental wellbeing in Maras et al (2015), and the delineation of the types of screen based activities in the screen based portion of the questionnaire.

There are many things that could cause the different findings in these two studies. Included in this could be external social and cultural differences that were not measured in the two different communities in which the studies were conducted that might be impacting student responses, the difference in the questions posed in the two different communities, bias of the researchers impacting the interpretation of the data collected, and the different intent in designing the two different studies with the intent of Ferguson (2017) examining risky behaviours and the intent of Maras et al (2015) examining mental wellbeing. In examining the two studies, I suspect the most likely cause for the contradictory findings between the two studies with regards to collecting data around depression is in the questions asked in the surveys with regards to depression. In Ferguson (2017) the scale used consisted of three items related to depressive symptoms. An example of one item was “During the past 12 months, did you ever feel so sad or hopeless almost every day for two weeks or more in a row that you stopped doing some usual activities?” Whereas in (Maras et al, 2015) they used a pre-established and tested questionnaire, the Children’s Depression Inventory (CDI), consisting of 27 items reflecting cognitive, affective, and behavioural signs of depression (Kovacs, 1992). Similarly for anxiety, they used the Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children, which is a 10-item, self-reporting scale that is a short and efficient global measure of anxiety symptoms (March et al, 1999). Having spent the past 6-years having to fill out such surveys regularly during treatments, post two car accidents, depression is complex and multilayered and requires more than 3 questions to assess. Assessing depression as “During the past 12 months, did you ever feel so sad or hopeless almost every day for two weeks or more in a row that you stopped doing some usual activities?” is more of an extreme scenario, and misses many other indicators of depression.

As such, after examining these two studies, I am more apt to give the data in Maras et al (2015) more credence. The only way, however, to scientifically test whether the difference in the two reports were based on the manner in which depression is being tested is to replicate the studies in the different communities. Using Ferguson’s scale, what results would be found in Ottawa? Using Maras et al’s questionnaire, what results would be found in Florida?

Have you discovered contradictory studies in your research? What were the potential causes of this?

Works Cited

Ferguson, C. J. (2017). Everything in moderation: moderate use of screens unassociated with child behavior problems. Psychiatric quarterly, 88(4), 797-805.

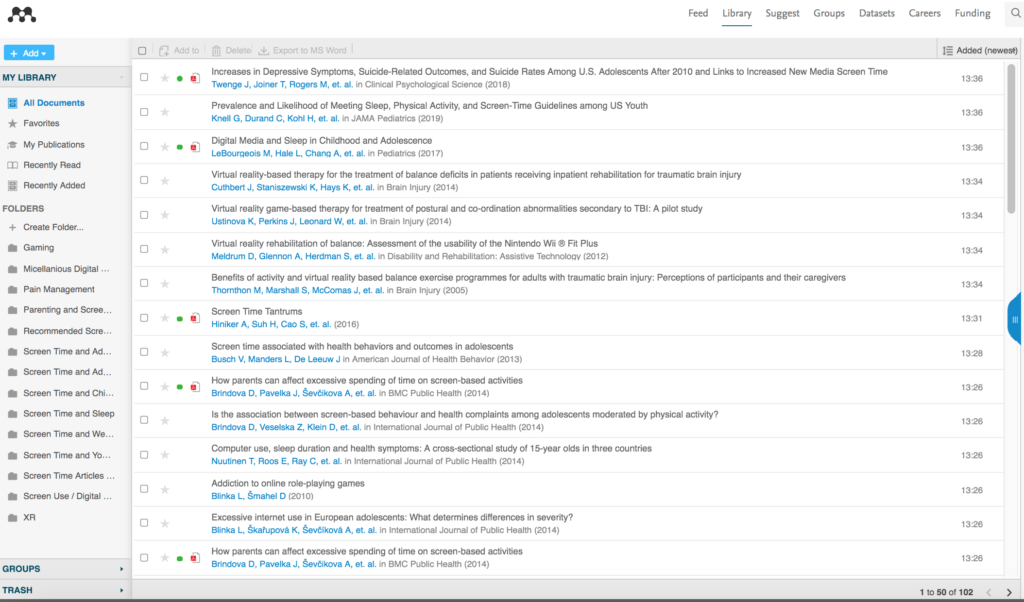

Hargreave, E. (2019, July 26). Researching Optimal Screen Time Limits for Classroom Activities for Different Screen Based Activities [Web log post]. Retrieved August 16, 2019, from https://ericahargreave.com/2019/07/researching-optimal-screen-time-limits-for-classroom-activities-for-different-screen-based-activities/

Kovacs, M. (1992). Children’s depression inventory: Manual(p. Q8). North Tonawanda, NY: Multi-Health Systems.

Maras, D., Flament, M. F., Murray, M., Buchholz, A., Henderson, K. A., Obeid, N., & Goldfield, G. S. (2015). Screen time is associated with depression and anxiety in Canadian youth. Preventive, 73, 133-138.

March, J. S., Sullivan, K., & Parker, J. (1999). Test-retest reliability of the Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children. Journal of anxiety disorders, 13(4), 349-358.

Przybylski, A., & Orben, A. (2019, July 7). We’re told that too much screen time hurts our kids. Where’s the evidence? The Guardian. Retrieved August 16, 2019, from https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2019/jul/07/too-much-screen-time-hurts-kids-where-is-evidence?